Diary of an NUS Museum Intern: Diyanah Nasuha

Note: Diary of an NUS Museum Intern is a series of blog posts written by our interns about their experiences during the course of their internships. Working alongside their mentors, our interns have waded through tons of historical research, assisted in curatorial work, pitched in during exhibition installations and organised outreach events! If you would like to become our next intern, visit our internship page for more information!

-

Hence, the research scope had been expanded to include regional developments of artistic styles, emergence of artists in response to the instabilities of post-WW2, with the rousing of nationalistic feelings and calls for independence by the colonies that were located in South-east Asia. My research was mainly focused on the emergence of abstract batik or ‘batik kontemporer’ during the 1960s to the 1980s within our region by Sarkasi Said, Yusman Aman and many Indonesian artists like Soelardjo, Soemihardjo, Bagong Kussudiarja and more. Thus, majority of the textual sources on these artists that I had worked with were either in Malay or Indonesian. One reason that I had to work with untranslated texts was because extensive coverage of such developments in this period were more-or-less confined to local Malay writers like A. Ghani Hamid as well as newspaper articles of the Berita Harian.

-

Diyanah Nasuha is a third-year Global

Studies student at the NUS Faculty of

Arts and Social Sciences. As our Lee Kong Chian Collection Curatorial Intern,

Diyanah was given the task to conduct research on mid-20th Century

art from the Malay Archipelago. Apart from research, Diyanah also attended a conservation workshop where she learnt about the conservation and restoration of

artworks.

My interests in museology, curatorship

and conservation only began recently when I had travelled to Egypt at the end

of 2015. Ironically, it wasn’t

the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo which had struck me, but it was my visit to the

Valley of the Kings in Luxor that had left an impact upon me. There and then,

it dawned upon me that one would not be able understand anything, from the

design of the tomb’s

layout, hieroglyphs to the specific usage of colors, if he or she did not have

any knowledge of Egyptology. Considering that not only photography was banned,

and even tour guides were unable to follow us into the tombs… so if one had completely zero

knowledge on the subject matter, honestly the site visit would be a highly

probable waste of precious time (plus the sheer distance one needs to travel

just to reach Luxor!!!!) and a devoid of meaning because the tombs were

essentially preserved as it was originally built and the only ‘sprucing up’ done by its custodians was the

construction of steep, rickety stairways that led into the underground chambers

and wooden platforms for visitors to tread upon. More notably, there was a

complete lack of signage within the tombs!

It got me thinking about what actually

goes into the setup of a museum; of things we often take for granted - layouts,

signage, trained docents etc which are more easily available in Singapore’s museums as compared to Egypt’s. Not only did I grapple with

the language barriers, the lack of information and the lack of ease of

obtaining answers to my endless amount of queries made me more aware, and most

importantly appreciative of the ‘comforts’ of the museums here. Hence,

all culminating to me becoming an NUS Museum intern.

Thus, for the past 10 weeks, I was the

Lee Kong Chian Collection Curatorial Intern at the NUS Museum. During my stint

as an intern, I was not only fortunate to see back-and-forth between the museum’s curators, Ahmad and Siang,

over the Lines : War Drawings and Posters from the Ambassador Dato’ N.

Parameswaran Collection exhibition’s

prepatory stage which had allowed for me to gain insight on what are the

considerations that curators keep in mind to their thought processes behind

curating. All this while, I assumed that curators were simply custodians of

their assigned collections but after interning at the museum, I’ve gained a more accurate

perspective on the role that curators take on within a museum.

As the Lee Kong Chian Collection

Curatorial Intern, I had worked with my supervisor Chang Yueh Siang, who is the

curator of the Lee Kong Chian Chinese

Collection, to research on an upcoming exhibition involving mid-20th century

art from the Malay archipelago. Initially thinking that the research process

would be a breeze since I had been instructed to focus on a particular Singaporean

artist, Sarkasi Said, this quickly changed after a meeting with the head

curator, Ahmad Mashadi, who shared his direction and vision on this upcoming

exhibit. Eventually, for the purpose of producing a series of artists

interviews for the upcoming exhibition. There and then, was only I made aware

of the unique position of the NUS Museum, of the need to have an educational

purpose behind their exhibits in order to not only reach to the general public,

but also to serve a purpose in academic research and scholarship. Thus,

avoiding grand, linear narratives that other museums may choose to adopt in

relation to curating an exhibition.

In the Resource Library with fellow intern Teen Zhen

Hence, the research scope had been expanded to include regional developments of artistic styles, emergence of artists in response to the instabilities of post-WW2, with the rousing of nationalistic feelings and calls for independence by the colonies that were located in South-east Asia. My research was mainly focused on the emergence of abstract batik or ‘batik kontemporer’ during the 1960s to the 1980s within our region by Sarkasi Said, Yusman Aman and many Indonesian artists like Soelardjo, Soemihardjo, Bagong Kussudiarja and more. Thus, majority of the textual sources on these artists that I had worked with were either in Malay or Indonesian. One reason that I had to work with untranslated texts was because extensive coverage of such developments in this period were more-or-less confined to local Malay writers like A. Ghani Hamid as well as newspaper articles of the Berita Harian.

Not only was this personally

challenging to me, because of my rusty second and third languages, but a lot of

the resource materials were only available in the archives of the National

Library Board and the National Gallery - which meant hours spent poring over

the online catalogues, selecting useful resources and making copies of the

microfilm and archival materials. This research topic was especially of

particular interest to me because of my identities as a Singaporean Malay and

being ethnically Javanese, the subject of batik is close to my heart and its

movement into being considered as fine art through the development of abstract

batik design had first emerged in Java, particularly in Jogjakarta and Jakarta.

Thus, this essentially allowed me to delve into my own culture’s art and history!

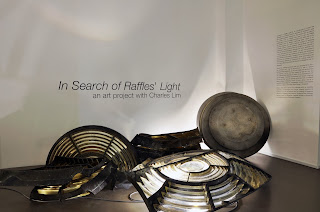

Other than that, thanks to Michelle’s connections and planning, we

were able to attend various curatorial tours, revelling together on the success

of the NUS Museum for being the ‘first

recipient of the University Museums and Collections (UMAC) Award for the most

significant innovation or practice that has proved successful in a university

museum or collection’ to

attending a Conservation workshop, where we learnt what goes into the

conservation or restoration of damaged artworks and more. The Internship

Dialogues and curated tours of the NUS Museum’s own exhibits gave us a platform for us to establish

discussion and bouncing back of ideas and views, which I found really enriching

because we were able to garner new insights from both my fellow interns and

curators. I had also really enjoyed the delicious food catered for the various

museum events and the opportunity to spend time with the other interns while

staying back to help out with the aforementioned events.

I am very grateful for this

opportunity to spend my summer at NUS museum, I am especially thankful to my

supervisor, Chang Yueh Siang, whom had patiently guided me even at times that I

was completely lost due to the lack of direction of my research and trusted me

enough to conduct independent research outside the office and university

spaces, to the other curators like Kenneth, Sidd and Ahmad, for their deep

insights on curatorship, museology to exhibition practice as well as the other

friendly NUS Museum staff like Michelle, Trina, Greg, Donald, Devi, Flora, JJ,

Philip, Jonathan, whom were all very welcoming and willing to answer my queries

and help wherever and whenever they could. Last of all, to my fellow interns -

Chu Tong, Joshua, Zhi En, Maryanne, Xu Xi and Teen Zhen for brightening up my

otherwise often, mind-numbing days of stressful research and keeping up with my

quirks!

My biggest takeaway from this

experience though, is definitely the potential development of my ability to

appreciate abstract and contemporary art as well as overall museum

appreciation. I learnt that art may not necessarily be solely created for the

purpose of beauty or aesthetics; but may be imbued with intangible meaning and

value, from the purpose of the preservation of eroding cultures to being a

medium to express popular sentiments and watershed developments of that time

period, all striving to resonate a deeper purpose to us who view it; where it

is highly possible that we ourselves are only scratching the surface when

trying to understand its true messages and meanings and aided by curators, who

contextualise such pieces through the construction of narratives for us to

garner some sort of understanding despite seeing these pieces with untrained eyes.

Comments

Post a Comment