Diary of an NUS Museum Intern: Mei En Gui

Note: Diary of an NUS Museum Intern is

a series of blog posts written by our interns about their experiences

during the course of their internships. Working alongside their mentors,

our interns have waded through tons of historical research, assisted in

curatorial work, pitched in during exhibition installations and

organised outreach events! If you would like to become our next intern, visit our internship page for more information!

As a student studying politics, sometimes I find it difficult to dissociate works of art from its political purpose and functions. The private collection of prints and paintings from the Vietnam War period really taught me to look before and beyond cynical politics which exists in every frame of time. Sometimes, these objects may be avenue of escapes for the common masses, where they find temporary peace and solitude in a haven, safe from the destructive social climate of their times. Sometimes, it may be an outlet of expression. Or maybe, these objects are (merely) a source of bread and butter. Yet, the presence of these visual records of brutality and humanity may spell doom for the artist. Perhaps this contradicting flux is yet another microcosm of the society we live in today.

I believe that one of the first sensations for a museum goer

is the silent exhalations of the beautiful objects. I realised that nothing is truly beautiful

even if beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder. Instead, we are most

interested in its deeds. The historian

is intrigued by the stories; the artists are intrigued by the techniques; the

intern is intrigued by all the labour behind the scene. We delve; we discover;

we are confused; yet at the end of the exhibition, we all seek to be

enlightened. Even if the sweetest turn sourest; we savour the bitter aftertaste.

In my four weeks, I barely had enough time to savour the aftertaste of anything. And it is in this period that my perspective of time and history was challenged, reinforced and recreated. I am thankful for my mentors and fellow interns who guided and accompanied me on this journey of exploration, making my time here such a fulfilling and enriching one.

In December 2014, 8 interns joined us to work with the

curatorial and outreach teams, conducting research for upcoming exhibitions and programmes in 2015 at the museum and the NUS Baba House. Besides those involving our collections and recent acquisitions, the interns prepared for upcoming exhibitions surrounding the work of alumni artists, the

T.K. Sabapathy Collection, as well as SEABOOK. They also assisted with ongoing happenings at the museum, including exhibition installation and programme facilitation.

-

Mei En Gui is a second-year student at the Department of Global Studies at NUS FASS. During her internship, she worked on research for Between Here and Nanyang: Marco Hsu's Brief History of Malayan Art, our upcoming Resource Gallery, as well as a prep room project surrounding Vietnamese war prints. The Between Here and Nanyang: Marco Hsu's Brief History of Malayan Art exhibition is currently open at the South and Southeast Asian Gallery on the Concourse level of the museum.

During the semester, I was exposed to the theories used by

Benedict Anderson in his book Imagined Communities. In this text, I was exposed

to several interesting thoughts. One of it was the idea of the simultaneity of

time (Anderson, 1991). It is said that

the people in medieval times had a different understanding of time. There was

no past, there was no future; there was only a continuous present. With the

invention of clocks and the reinforcement of their use during the Industrial

Revolution, we are more familiar with the concept of the past today. The museum is

a labyrinth; we could find the past in its rarest form. Their timeless beauty,

their arrogance, their majesty, their wretchedness were all encased in a time

machine. Stepping into one was akin to

being transported into a dimension where one could exist in a time simultaneous

with the artist or the merchant. The simultaneity of time is no longer a

privilege of the past, as claimed by Anderson, when we step into a museum.

I was first tasked to find out the different symbolism of

the different motifs used in the decoration of chinaware. Beyond history, I had

learnt about the attitudes of the Chinese. Working on Marco Hsu's Brief History

of Malayan Art gave me insights into how artists and curators cannot function in

an isolated time frame from the other (even if the artist is deceased). I was

put in a position where I had to research on the times of tumult which the

artists lived in back then. It seems we will not fully comprehend the

emotions behind a piece of work if we cannot put ourselves in the same social

climate as they had lived in. The only way to imitate as such was through

imagination, aided by voracious reading. And the most delicate object put up in

an exhibition, as I thought, would perhaps be the emotions behind every piece

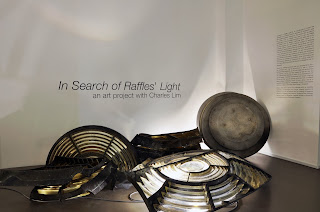

of work. When I stepped into the Curating Lab exhibition, an initiative to

expose budding curators to the work of a curator, it was a moment of conflict.

I thought: how different is a piece of artwork different from a piece of

history? Are they in fact subsets of each other? Perhaps a piece of history

would become a piece of art when it loses its social purpose for the people in

that sphere of time.

|

| The colonial map of Singapore and Johor in 1954, something which I’d chanced upon while reading an annual report for the Marco Hsu project |

As a student studying politics, sometimes I find it difficult to dissociate works of art from its political purpose and functions. The private collection of prints and paintings from the Vietnam War period really taught me to look before and beyond cynical politics which exists in every frame of time. Sometimes, these objects may be avenue of escapes for the common masses, where they find temporary peace and solitude in a haven, safe from the destructive social climate of their times. Sometimes, it may be an outlet of expression. Or maybe, these objects are (merely) a source of bread and butter. Yet, the presence of these visual records of brutality and humanity may spell doom for the artist. Perhaps this contradicting flux is yet another microcosm of the society we live in today.

|

| “For sweetest things turn sourest by their deeds; lilies that fester smell far worse than weeds.” |

In my four weeks, I barely had enough time to savour the aftertaste of anything. And it is in this period that my perspective of time and history was challenged, reinforced and recreated. I am thankful for my mentors and fellow interns who guided and accompanied me on this journey of exploration, making my time here such a fulfilling and enriching one.

References

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflections on

the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

Comments

Post a Comment